Arts & Culture 2024

Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art is a Lesson in Contrast

December 2, 2024

Arts & Culture 2024

Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art is a Lesson in Contrast

December 2, 2024The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Photo © Maja Wirkus, courtesy MSN

Warsaw’s Plac Defilad (Parade Square) has a complicated history. Built by the Soviets amid the ruins of World War II, the vast space—the largest public square in Europe—was used for propaganda rallies and to host a Papal visit in 1987. Post-communism, it included a makeshift bus station, food kiosks, and market halls, and was the site of clashes with police over the latter’s removal. Its land was the subject of several lengthy legal disputes involving the reprivatization of real estate. Dominating the Plac Defilad is the ornate Palace of Culture and Science, which Stalin “gifted” to the people of Poland. Even seven decades later, its 760-foot-tall tower is one of the most prominent features of the skyline. (Only a two-year-old office tower by Foster + Partners is taller.)

But now, this fraught landscape has a new addition—a home for the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, also known as the Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie (MSN). Designed by New York–based Thomas Phifer, the long and low white building, in pristine poured-in-place concrete inside and out, sits on the eastern edge of the square, facing a busy commercial thoroughfare. Together with a short prismatic “tower” containing a stair to MSN’s basement-level cinema, the museum’s volume acts as a quiet but forceful foil to the showy Palace.

1

2

The minimalist facades of MSN (1) contrast with the ornate Stalinist tower beyond (top of page). The museum has its own “tower” (2), providing access to a basement cinema. Photos © Nate Cook, click to enlarge.

Punctuated with a few well-placed apertures and articulated with an arcade at the base and a horizontal slot containing a ribbon of windows at its midsection, the 213,000-square-foot MSN opened in late October with a three-week cultural festival. (Fully installed galleries will open in February.) It is the first piece of an emerging arts district on the square, which will also include a park by the architecture collaborative A-A Collective, now under construction, and a black steel-plate-clad cubelike building for the TR Warszawa Theater, in the early stages of site work. The theater commission, as well as that for the museum, were won as a pair by Phifer’s firm in a 2014 competition, the third held for the MSN project since the institution’s founding in 2005.

3

4

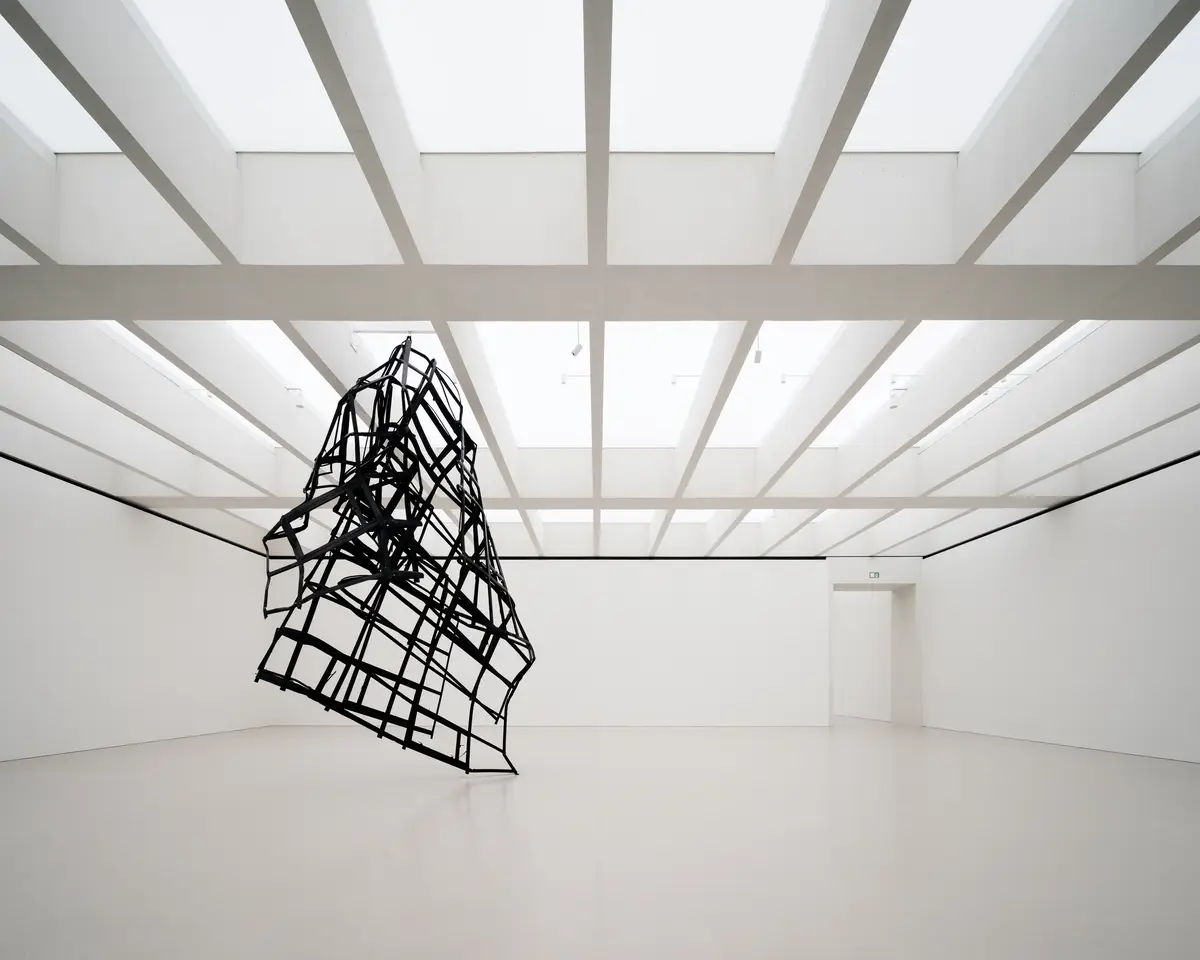

Pieces by Sandra Mujinga (3) and Monika Sosnowska (4) were among several large-scale works, all by women, installed for the October opening. Photos © Nate Cook

Phifer is known for his minimal but precisely detailed spaces for art, including Glenstone, near Washington, D.C., conceived as a series of pavilions in a verdant landscape. But in Warsaw, the crisp, pared-down aesthetic and his choice of material were strategies for making a structure that would “hold its own” in the challenging context. In addition, he wanted to create a “strong sense of permanence” for the relatively young and previously nomadic MSN, established with the mission of collecting and presenting international art made since 1989, the year Communism fell in Poland and much of the former Soviet bloc. The building, Phifer says, “needed to have weight.”

The $175 million project, funded by the city, was conceived as a venue where people would come together and exchange ideas—a role with new relevance in the wake of the eight-year rule of the country’s nationalist right-wing Law and Justice party. “We wanted a place for discussion, debate, and the contemplation of art,” says Joanna Mytkowska, the museum’s director. Toward that end, the ground floor, which houses a café, a bookstore, and a space for experimental and quickly changing exhibitions, will be open to all and accessible without a ticket. It also features an “auditorium”—a perfect square, defined by the eight columns surrounding it and by a recessed floor, though it is otherwise open to the rest of the lobby level.

The ground floor’s main event, however, is a heroic skylit stair leading to the two gallery levels above. Square in plan, like the auditorium, the stair’s twinned runs seemingly float—a sleight of hand enabled by hidden hollow steel sections connecting them to perimeter columns—and meet at landings at diagonally opposite corners. Phifer calls it a “social space,” citing precedents such as the grand staircase at Charles Garnier’s Paris Opera. The MSN version functions not only as a place to see and be seen, but also as a sculptural stage for experimental dance or improvisational performances.

5

A sculptural stair, with seemingly floating twin runs, provides a place to see and be seen (5 & 6). Photos © Beata Klebanska (5), Nate Cook (6)

6

In contrast to many museums designed over the past decade or two, MSN did not desire ultra-flexible galleries that could constantly be transformed. Instead, according to the architect, Mytkowska wanted fixed spaces that would themselves “serve to curate the art.” Organized into two suites on each of the two gallery levels, the rooms are of varying sizes and ceiling heights that range from 13 feet to nearly 24 feet tall. Except for some smaller rooms intended for sensitive works or video, almost all are daylit. Those on the uppermost level are top-lit through a system that combines fixed louvers, a triple-glazed skylight, and a stretch-fabric ceiling, delivering a diffuse and even level of illumination. Second-floor galleries, meanwhile, are daylit from the side via 40-inch-tall clerestory windows—housed in the slot surrounding the facade—offering light with dynamic and noticeably changeable qualities and a connection to the outside. “Visitors will feel the difference with the changes in season and times of day,” says Phifer.

A “city room” offers visitors a place to pause. Photo © Nate Cook

Museumgoers will have an even more direct connection to the exterior environment in “city rooms,” narrow chambers inserted within each sequence of galleries, with every surface—walls, floors, and ceilings—clad in ash wood from the region. Each contains a bench, in the same warm-hued timber, positioned in front of an oversize window, offering a spot to take in a view of Warsaw. “It’s a space for pause and reflection,” says Phifer, “an opportunity to place yourself in the city.” These rooms also provide an appreciation of the building’s solidity—the window openings revealing the impressive 7-foot depth of the exterior-wall assembly, encompassing envelope, structure, and services.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

This sense of heft is also evident in the building’s exactly formed concrete structure, whose configuration was largely dictated by the conditions below grade, producing a rhythm of transfer beams and column grids that sidestep a subway station and its tunnels (and necessitating that the building sit atop bearings and anti-vibration mats). Maintaining the perfection of the exposed concrete was demanding, points out Zbigniew Czajewski, a partner in the Warsaw office of Buro Happold, the project’s consultant for several disciplines, including that of building structure and its mechanical systems. Just one of many challenges was the careful coordination of services so that no ducts, vents, or access hatches are visible, he says.

The engineering behind the poured-in-place concrete facade was equally exacting, especially given the aesthetic goals: an almost monolithic appearance in elevations that are more than 300 feet long, and an impression of weightiness, despite being lifted off the ground. The main concern was unsightly cracking. So, serving as facade consultants, structural engineers from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) broke the skin down into segments, with as few joints as possible, and devised a system for attaching the panels that includes a “haunch” for where they sit on the structural slabs. The connection incorporates bearings, there to allow for wind forces and thermal movement rather than mitigate subway vibrations, notes Stuart Marsh, a senior associate principal in SOM’s London office.

The level of care taken with the facade is characteristic of the attention to detail found throughout the building, creating an ideal backdrop for the art it will display, a destination for visitors to Warsaw, and a safe space for Varsovians and others to come together to freely exchange ideas. Its austerity, too, is an apt response to the charged environs, offering a counter to what came before while looking to the future, establishing an anchor for the emerging cultural quarter taking shape around it.

Architects & Firms

Click plan to enlarge

Click plans to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Click diagram to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Thomas Phifer and Partners — Thomas Phifer, director; Katie Bennett, project director; Gabrielle Marcoux, Steve Dayton, Michie Yahagi, Andrea Machado Romero, Wiktor Kazimierczak, Gabriel Smith, Ryan Connolly, Chris SooHoo, Leticia Wouk Almino Kim, Alexandria Lee, Anna Fritz, Justin Fan, Agata Kolwas, Jakub Barwiński, Anna Kaertner, Jessica Luscher, Brittany Utting, Greg Bonner, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, Jiaxing Yan, Evan Yoon, Remon Alberts, Matthew Zuckerman, Lauren Eggert, project team

Local Architect:

APA Wojciechowski Architects

Consultants:

Buro Happold (m/e/p, civil, structure); Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (facade); Arbo, Struktura (facade engineer of record); Arup (daylighting, lighting); TBAIS (architectural concrete)

Owner's Representative:

Paratus Group

General Contractor:

Warbud

Client:

Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN)

Size:

213,000 square feet

Project Cost:

$175 million

Completion Date:

October 2024

Sources

Architectural Concrete:

Warbud

Formwork:

ULMA Construccion Polska

White Cement:

Danucem Slovensko

Glazing:

Saint-Gobain

Skylights:

Jansen, RH Plus, Dormakaba, Aluminium M, Assa Abloy

Roof Louvers:

Granit

Lighting:

Litelab, Glamox, Zumtobel, Wästberg, Viabizzuno

Dimming system:

Gira