Architects & Firms

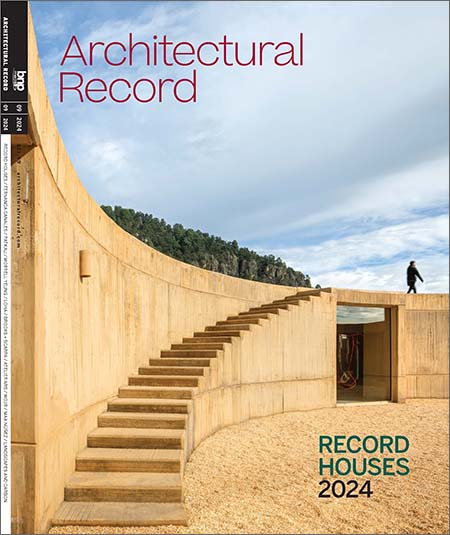

Before the Mexico City–based architect Fernanda Canales put pen to paper to design what would eventually become the striking Casa 720—a country house for a family of six set on 3.7 acres, about 90 miles southwest of the Mexican capital—she erected three wood platforms connected to the ground by rickety wood stairs: “tree houses,” Canales says, “without a tree.” The lot, traversed by a dense line of mimosa shrubs, sprawled beneath a soaring basalt crag, its edges fringed by primeval forests of live oak and pine. Canales used the platforms to experience the view from what would eventually be the house’s green roof, ultimately identifying the ideal spot, toward the middle of the lot, where neither the nearest neighbor nor the rock formation would feel too close. As Canales studied the land, her clients, Rodrigo Moreno and Lorenza Pallares, used the platforms for afternoon picnics looking out to the crew-necked silhouette of the Nevado de Toluco volcano and for cool nights of star-gazing under a pointillist sky.

Photo © Rafael Gamo

Canales knew the area well, and particularly the development, called Reserva Peñitas, where Moreno and Pallares had purchased their lot. Prior to meeting the couple about seven years ago, Canales had built two other houses within the Reserva, called Casa Bruma and Casa Terreno (Record Houses in 2018 and 2019). At the earliest stages of work on Reserva Peñitas in 2008, developers brought on Taller de Operaciones Ambientales (TOA)—Workshop for Environmental Operations—a multidisciplinary office focused on planning and sustainability. TOA laid out a master plan for the subdivision that set aside half of the 470 acres for common areas and a forest reserve threaded with 10½ miles of hiking trails. On the remaining land, divided into 80 “ranches,” residents could build on no more than 7 percent of their lots, following strict guidelines for materials, height, landscape, and water use, all supervised and approved by an oversight committee.

1

Panels of floor-to-ceiling glass swivel to provide access between inside and out (1 & 2). Photos © Edmund Sumner

2

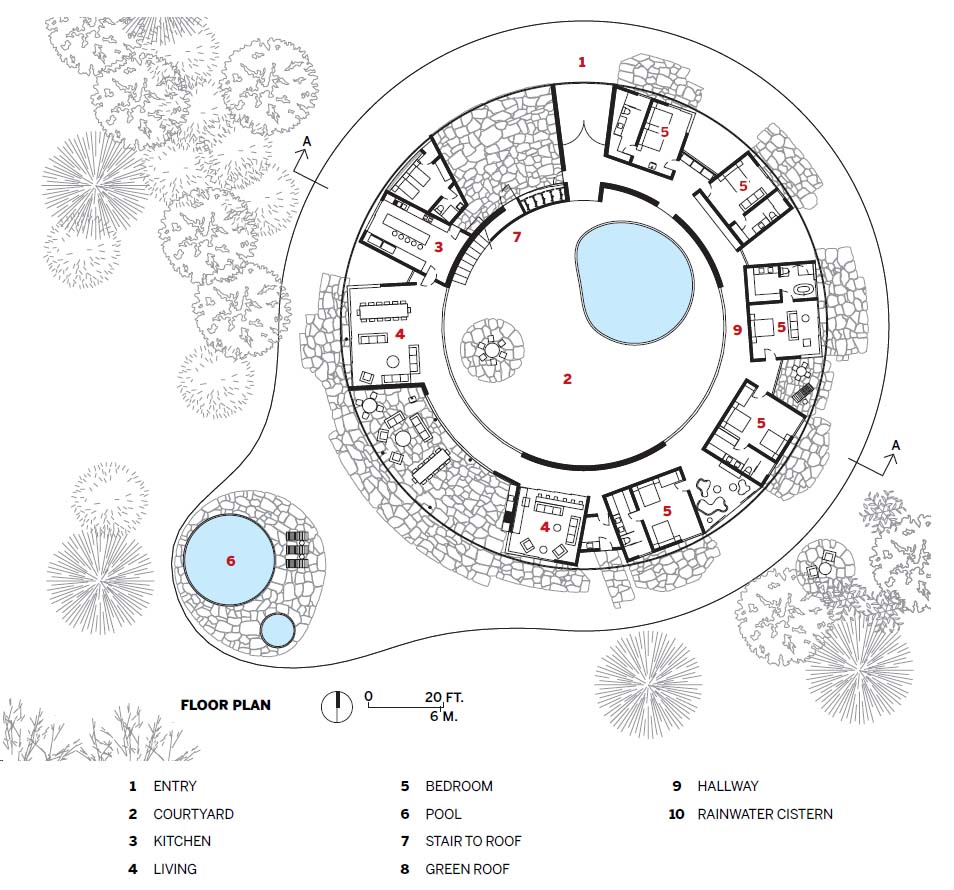

In leveling the terrain and transplanting the mimosas to its edges—a manipulation of the landscape that she undertook reluctantly—Canales “discovered these views that you couldn’t see before or that hadn’t existed.” It became clear, Pallares says, “that there was no obvious way to orient the house toward just one view.” And so, in 2019, Canales presented Pallares and Moreno with her first daring proposal: a circle of rough concrete, tinted a pale sienna with stone extracted from the site and organized around an austere interior patio.

3

The concrete used for the main structure is tinted a pale sienna by stone extracted from the site, making the house feel inseparable from its surroundings (3 & 4). Photos © Camila Cossio (3), Rafael Gamo (4)

4

The 3.7-acre property includes a separate studio building. Photos © Rafael Gamo

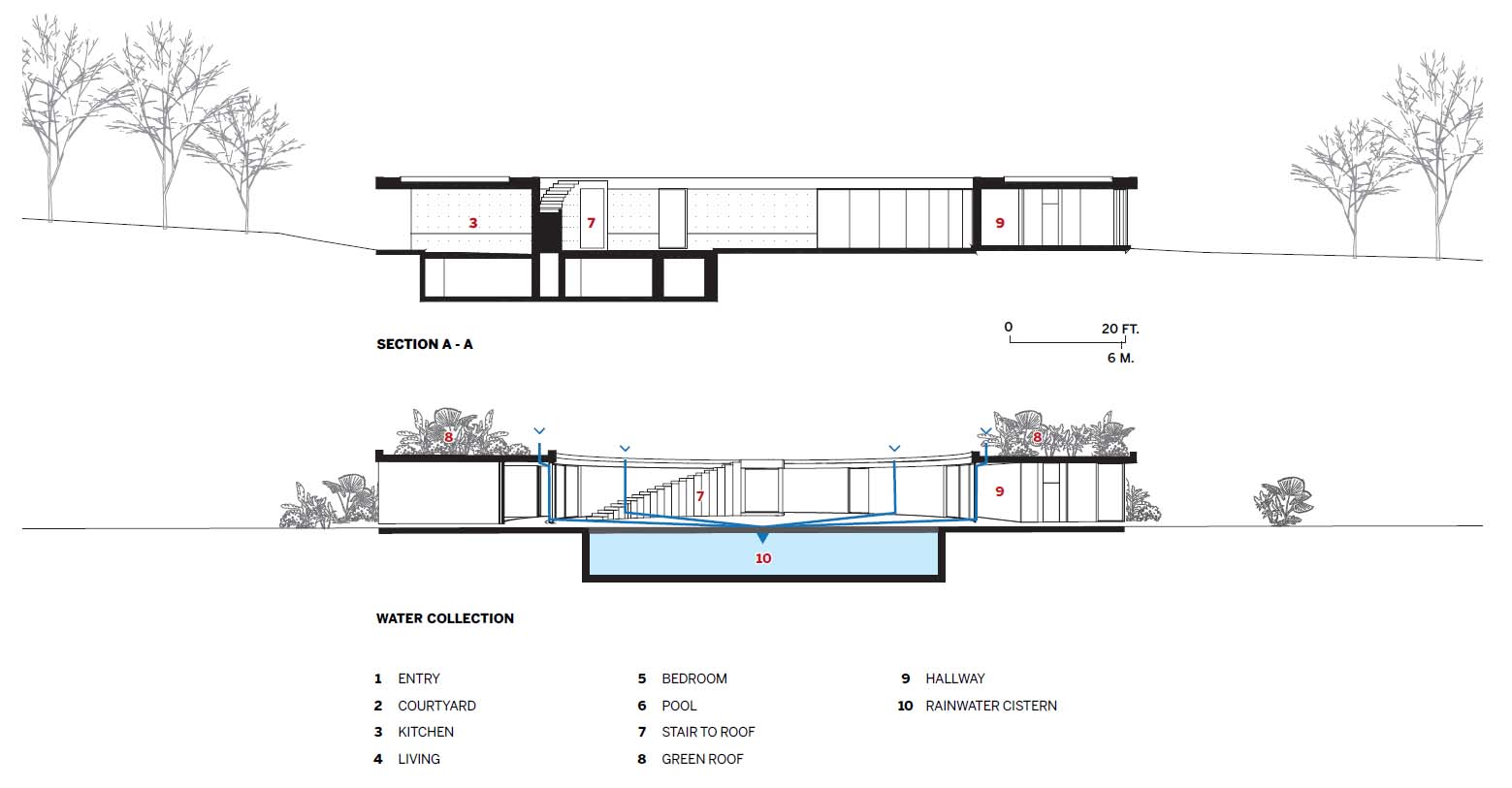

During the years of the pandemic, what began as a single-family holiday retreat expanded into a second home, with a separate studio space for Moreno and bedrooms to accommodate visitors and a large extended family. But the project’s fundamentals went unchanged. To avoid the discomfort and inconvenience of curved walls, Canales designed the house as “a play of two geometries,” she says, placing a sequence of orthogonal rooms between the circular floor plate and rooftop. Sinking the roof below the lot’s entry height and tinting the walls to match the color of the rock face helped the building disappear into its surroundings, while simple construction, executed almost entirely by an extended family of local builders, lends the structure a rough-hewn modesty that helps to contrast with its scale, measuring more than 130 feet in diameter. Textures, colors, and materials, limited here to concrete, wood, glass, and stone, draw on the same palette that Canales uses throughout her work, whether designing country homes like Casa 720, apartment buildings in Mexico City, or public infrastructure like libraries, cultural centers, and reading rooms in marginalized communities.

5

6

A limited palette of concrete, wood, glass, and stone ties together outdoor (5) and indoor (6) spaces. Photos © Rafael Gamo

Like Canales’s previous houses in the Reserva, Casa 720 explores the potentialities of the central patio, a fundamental typology in Mexican architecture, from colonial courtyard houses to multifamily tenements and graceful Modernist projects by luminaries like Mathias Goeritz and Luis Barragán. Here, the permeable central patio, built over a 79,000-gallon cistern, captures water during the six-month rainy season for use throughout the year. By day, the same patio serves as a meditative central core, in contrast to the natural spectacle outside. By night, when the forest becomes “a wolf’s mouth,” Pallares says—pitch black, inscrutable, even unsettling—“the house turns inward,” with the patio as a luminous refuge from the darkness.

7

8

Orthogonal rooms (7) connect to arcs of hallway in the circular plan (8). Photos © Rafael Gamo

Though the house has no definite “front” and prioritizes no one view over another, its interior unfurls around a specific visual narrative. Heavy oak cathedral-style doors—built with a central portal for festive occasions and lateral entrances for daily use—open into a quiet vestibule with a floor-to-ceiling picture window that reveals nothing but the graveled courtyard and the far side of the structure. To the left, a hallway bends out of view, its curved inner wall lined with concrete, its straight outer perimeter delineated by bedrooms and paneled in oak. Progressing along the corridor, a pane of glass allows a first, partial glimpse of the mountain, which comes into full, spectacular view moments later through a sweep of floor-to-ceiling windows that pivot open to provide generous cross-ventilation—essential in a place where temperatures can fluctuate by more than 50 degrees from dawn to midday.

Given such gestures toward sustainability, critiques around the use of concrete are, perhaps, inevitable. Yet they also fail to consider the shortcomings of Mexico’s timber industry, controlled, in no small part, by organized crime. “To build with wood meant importing from Canada or buying wood from the forests that you can see being illegally cut down right in front of you in the surrounding area,” Canales says. Sustainability often means doing the best one can under less than ideal circumstances—a logic that also applies to create an ecologically responsible respite from the frantic pace of urban life at a time when any unnecessary construction is, strictly speaking, antithetical to that goal. The only truly sustainable second house, after all, is the one that goes unbuilt, that never becomes more than a scaffold open to the sky. What a project like Casa 720 can do—with its bold sculptural form tempered by remarkable humility before its surroundings—is turn our attention outward toward the mountains and forests, which are never as eternal as they seem.

Click plan to enlarge

Click sections to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Fernanda Canales — Fernanda Canales, prinicipal; Aarón Jassiel, Alberto García Valladares, Ángela Vizcarra, project team

Engineers:

Grupo Sai (structural), Gerson Huerta; Grupo MEB (sanitary and electrical), Carlos Medina

Consultant:

Camilla Pallares (interior decoration)

General Contractor:

Felipe Nieto

Clients:

Rodrigo Moreno and Lorenza Pallares

Size:

12,000 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

September 2023

Sources

Carpentry and Doors:

Oscar Nieto

Lighting:

Lucas Salas

Windows:

Venster, Alejandro and Mauricio Rojo

Floor and Wall Tile:

Marmoles Arca

Photovoltaic System:

Federico Buelink

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!