Civic Architecture 2024

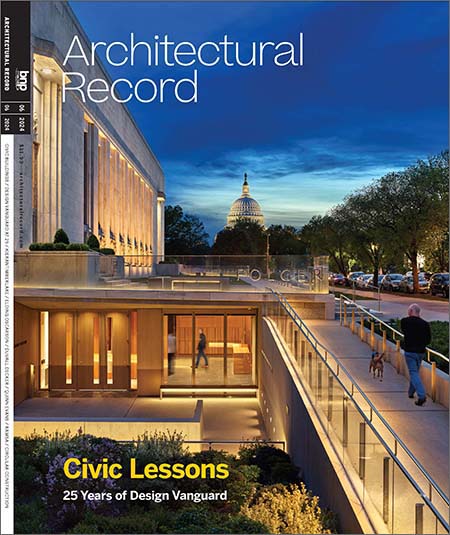

KieranTimberlake Transforms D.C.'s Folger Shakespeare Library

June 3, 2024

Civic Architecture 2024

KieranTimberlake Transforms D.C.'s Folger Shakespeare Library

June 3, 2024A replica of the statue of Puck inside is located between the west gardens, where other artwork includes a poem by Rita Dove inscribed upon the garden wall. Photo © Alan Karchmer

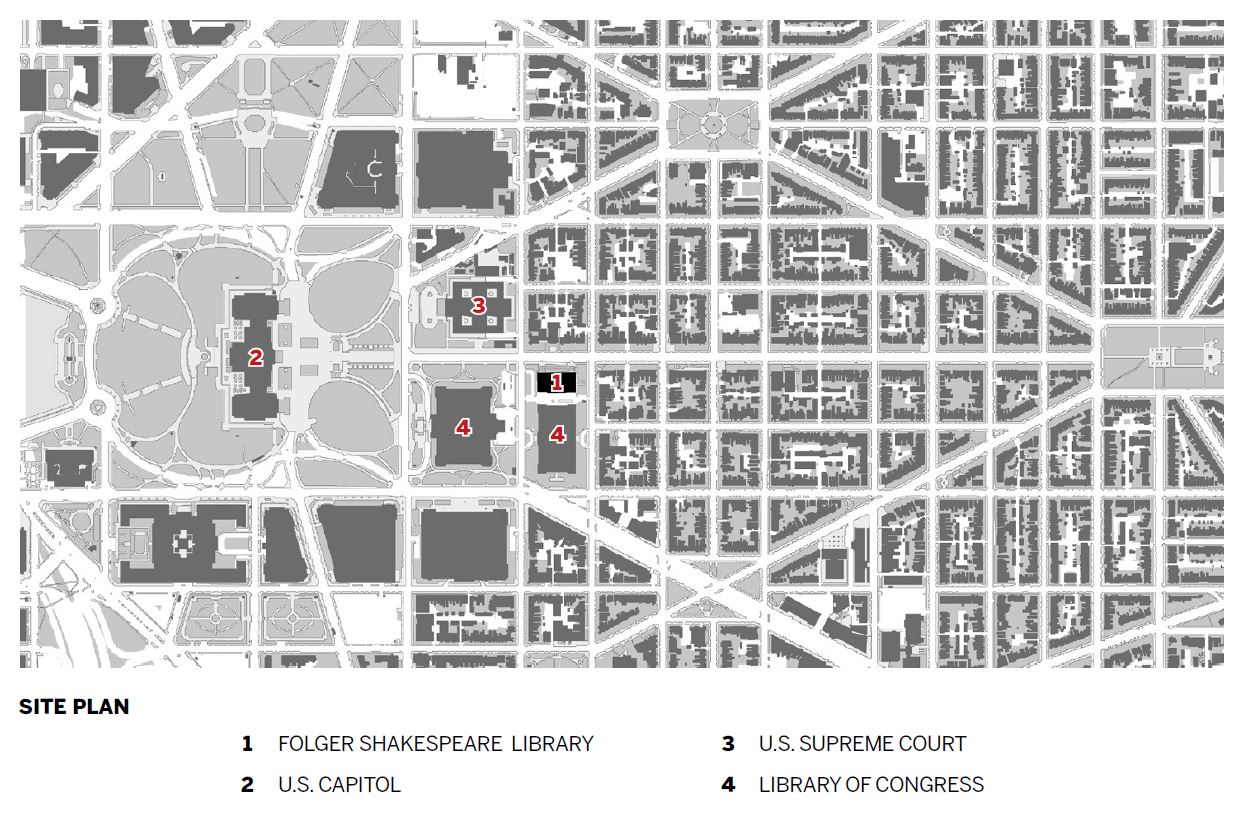

“Shakespeare has had many different interpretations over 400 years,” says Michael Witmore. “The same can be done with a building.” Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library since 2011, Witmore has overseen the transformation of the Folger’s nearly century-old home in Washington, D.C., which reopens to the public this month after a four-year closure. Designed by Paul Cret and completed in 1932, the stripped-down Neoclassical monument—built as a functional memorial to both the Bard and to Henry Clay Folger, who established what has become the largest collection of the printed works of Shakespeare, but who died soon after the cornerstone to his library was laid—fits right in with its immediate neighbors on Capitol Hill, which include the Library of Congress and the Supreme Court. “We want to lead in research,” says Witmore, “but also as a cultural institution that greets the public.”

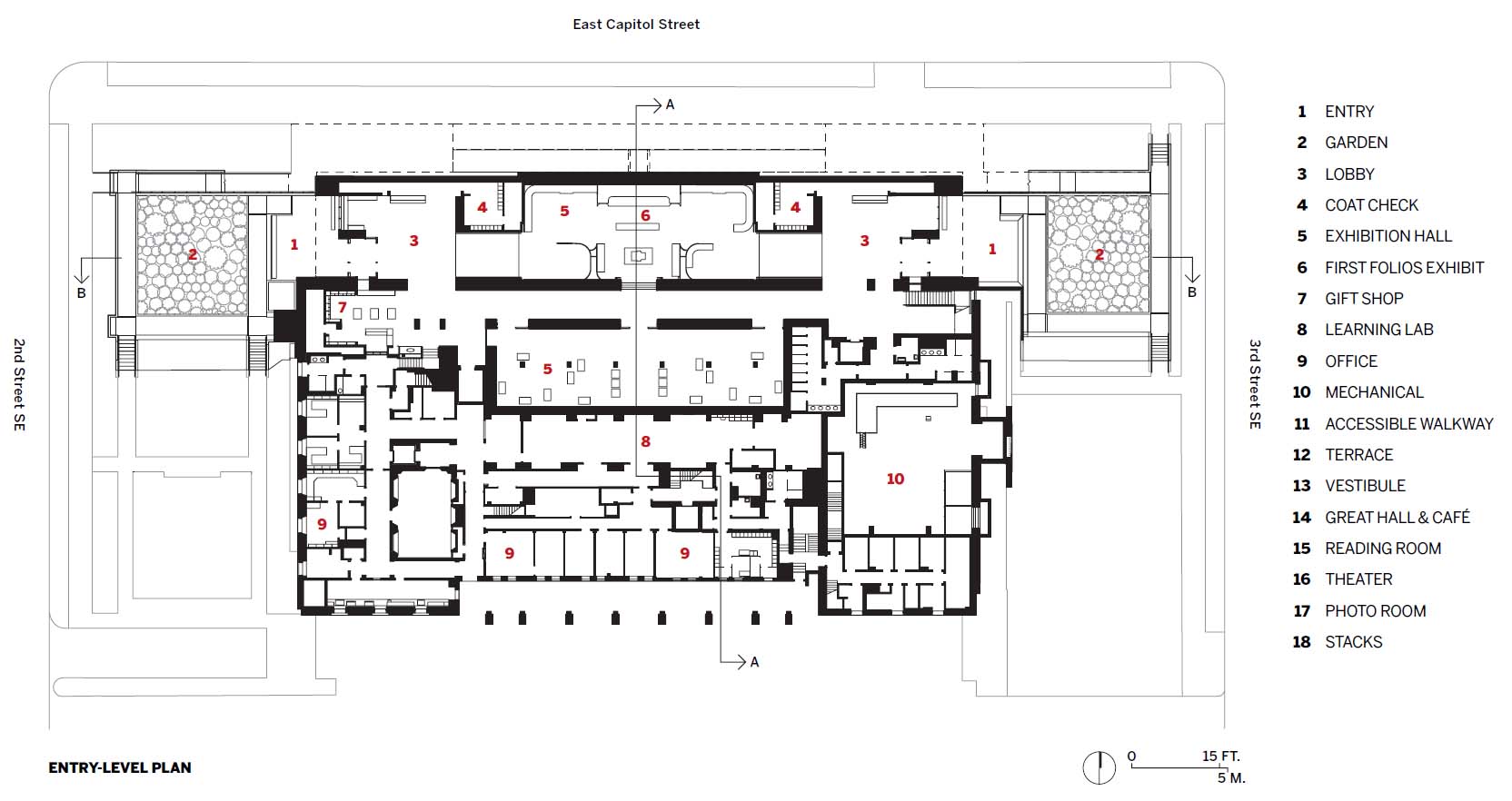

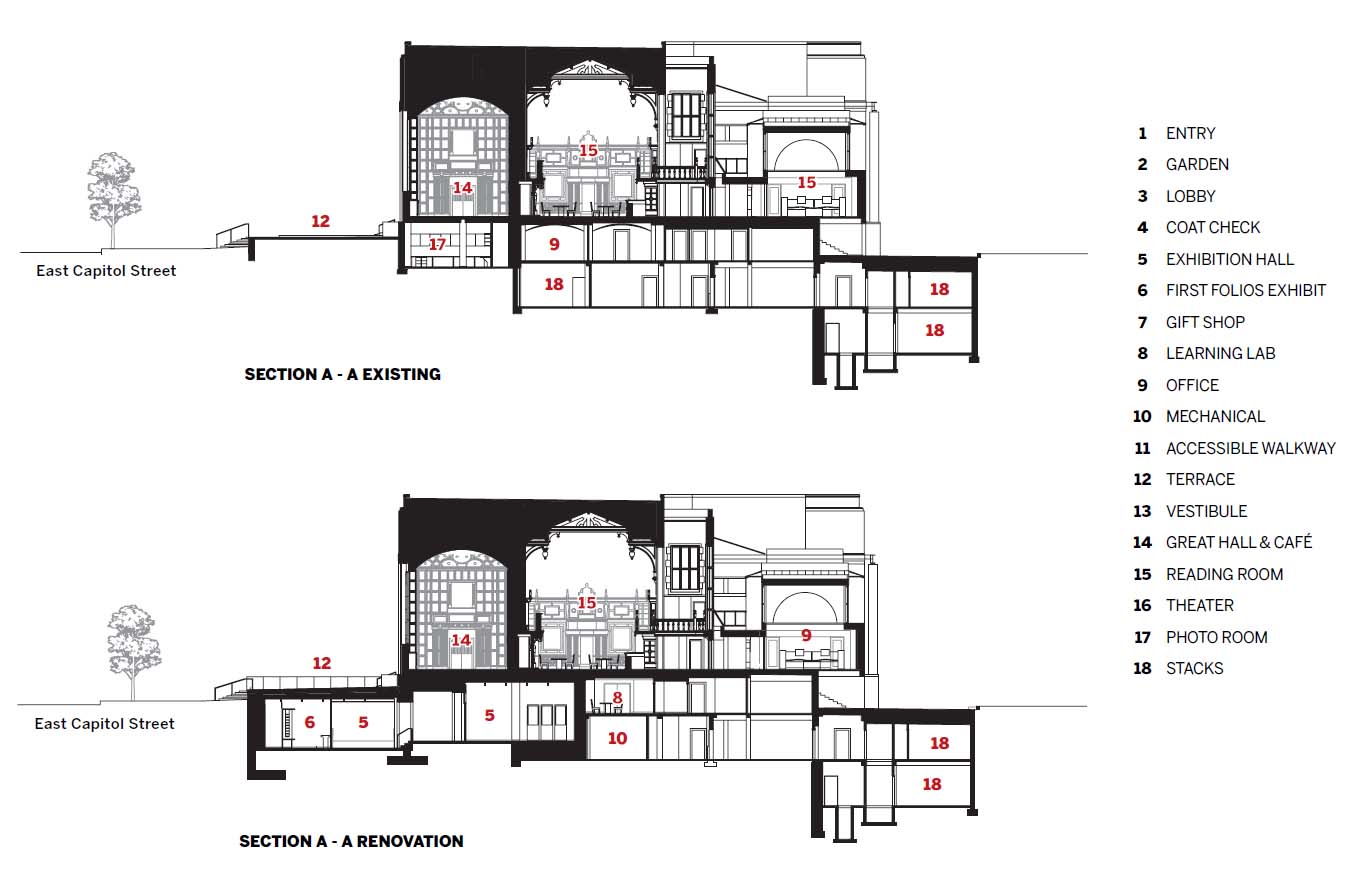

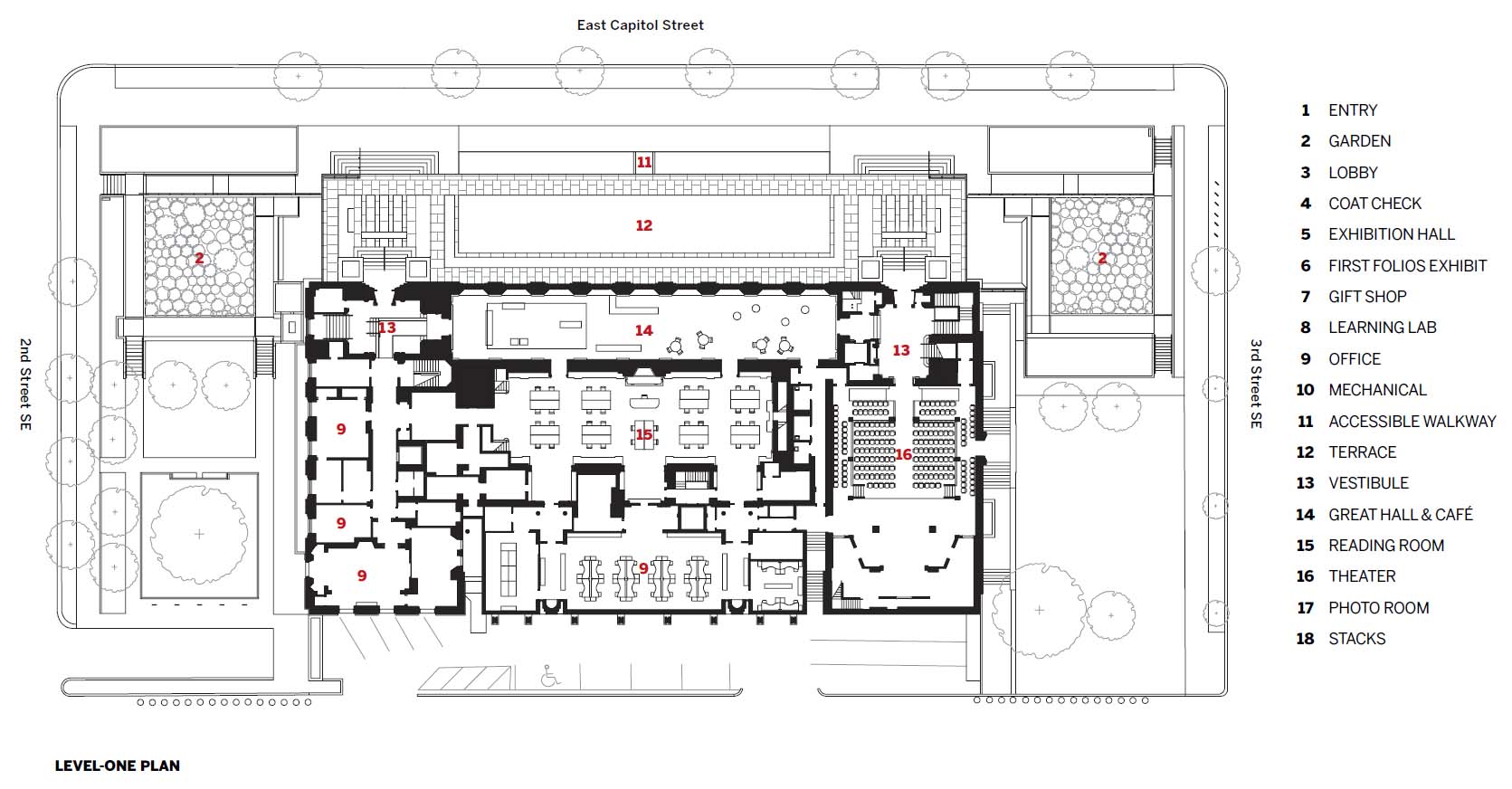

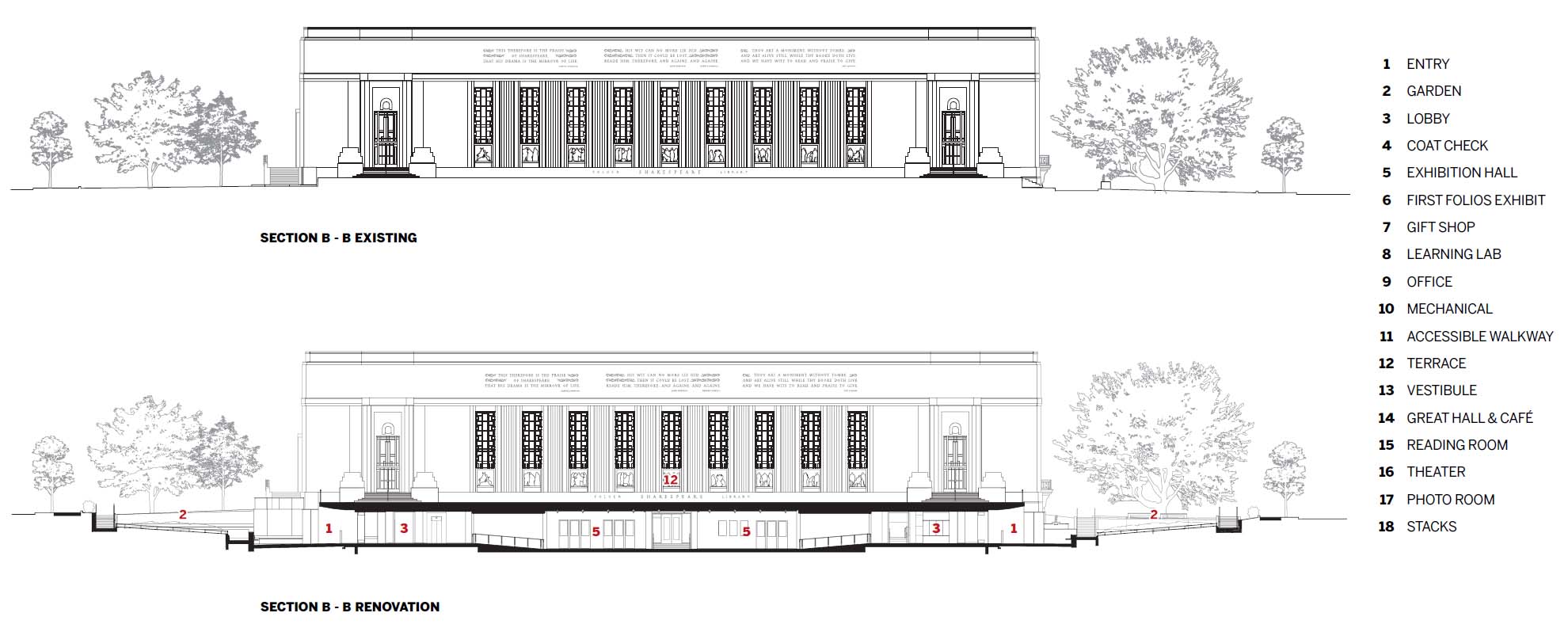

But how do you renovate and add to a landmarked building—it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, a designation that was expanded in 2018 to include its Tudor interiors and Elizabethan theater—on a small lot that has already seen previous additions, including one in the 1980s at the rear of the structure, by Hartman-Cox Architects, that is reportedly seeking its own landmark status? To that end, KieranTimberlake was initially hired for strategic planning services to envision a more inclusive, experiential, and welcoming place. More than 10 years on, the Philadelphia-based firm has overhauled the steel-frame building, most significantly its entry sequence, by digging under it.

1

2

At-grade and sunken gardens feature seasonally diverse shrub plantings (1) and lead to the new entrance (2). Photos © Alan Karchmer

The existing building offered several obstacles to access for those with disabilities, including a series of steps to get to the main level—where the former entrance and the grand public spaces like the theater, the Great Hall, and the reading room were located—additional steps in the interior, and public restrooms on the lower level reachable only by stair.

“This is a building of great rooms,” says KieranTimberlake partner Stephen Kieran. “We modernized the three historic rooms, but in a silent way. And we created the gardens as outdoor rooms.”

Working with landscape architect OLIN, and having received approvals from the adjoining residential neighborhoods, the District of Columbia, and federal authorities, KieranTimberlake moved the main entrance beneath the existing plinth at the front of the building. One arrives there through a series of ramps and walkways cutting through and enclosing square memorial gardens, which provide, as the architects put it, “both quiet and reflection as the visitor moves from the city into a previously hidden world.”

A series of ramps and walkways offers access to the Folger’s new entrance. Photo © Alan Karchmer

The 6,000-square-foot below-grade addition beneath the historic terrace contains a vast lobby with Jet Mist granite floors, sandblasted-concrete walls, and white oak and blackened-steel accents; side-by-side exhibition halls including one for the library’s prized First Folios; plus a learning lab, gift shop, and offices. A statue of Puck from A Midsummer’s Night Dream invites visitors to take the stairs to the upper level, which is accessible also by elevator. “The elevator does a lot of work with one move,” says Kieran.

3

4

The lobby features concrete, wood, stone, and steel accents (3). The First Folios are on display in the new north exhibition hall (4). Photos © Alan Karchmer

But the big move, of course, was excavating 13,740 cubic yards—just under 20,000 tons—of earth, bringing the new slab below the existing foundation in some places, and doing so without conventional underpinning. During the feasibility study, KieranTimberlake worked with the contractor on means and methods. “The stone facade had to be temporarily supported with steel elements while portions of the existing building structure were removed and supported with new steel structure and new concrete foundations,” says principal-in-charge Johann Mordhorst. “That’s generally the contractor’s responsibility to figure out, but we coordinated closely on constructability, rather than just cost-estimating.” And not only is the Folger located within D.C.’s monumental core, its addition is in “public space” beyond the Folger’s property line, requiring further review.

Artist Anka Neumann created a hanging work for a new stairwell. Photo © Alan Karchmer

The below-grade addition—with ceilings as high as 14 feet in the south exhibition hall—contains an extra 5 feet of ductwork beneath parts of it, necessitated by the expanded scope of the project that occurred in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. The team decided that it was best to tackle issues concerning day-to-day maintenance and mechanical upgrades at that point, instead of later. Two large coal-fired boilers beneath the theater originally provided heat to the building. That was later replaced with steam. Air-conditioning was supplied during the Hartman-Cox project. Now 18 different air handlers and a chilled-water loop do the job. (Providing displaced air below the seats of the theater required coring the structural slab.)

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

With those major hurdles overcome, the architects focused on interior enhancements, including inserting a café in the Great Hall, which previously contained the exhibitions. They removed the panels that covered its windows, which, on the exterior, showcase one of the earliest uses of aluminum as ornament. The Folger, on the other hand, had the task of moving its collection off-site to multiple locations, and bar-coding every single book, which had never been done before. Compact shelving was added to the stacks, which, in total, comprise 27,500 linear feet.

On Thursday, March 5, 2020, the Folger closed its then-last theater production and hosted a staff party. That Friday, it sent everyone home for three years. For the Folger, and KieranTimberlake, it’s been a long journey. For historic buildings, accessibility often equates to a “back door,” and preservation can be punitive. This project offers an alternative—without any changes to Cret’s original elevations—and a way forward for institutions seeking to grow but contending with limitations.

Architects & Firms

An archival photo shows the Folger’s original facade, which remained unchanged in this renovation, Photo courtesy The Folger Shakespeare Library

Click plan to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

KieranTimberlake — Stephen Kieran, design partner; Johann Mordhorst, principal in charge; Paul Worrell, Jordan Teitelbaum, project architects

Landscape Architect:

OLIN Studio

Engineers:

Silman (structural); Sorba Engineering (civil); Altieri (m/e/p, fp)

Consultants:

Studio Joseph (exhibition design); Shen Milsom & Wilke (acoustics); Tillotson Design Associates (lighting); Pentagram (graphic design and wayfinding)

General Contractor:

Gilbane

Client:

Folger Shakespeare Library

Size:

34,000 square feet (renovation); 6,000 square feet (below-grade addition)

Cost:

$54.5 million (construction)

Completion Date:

March 2024

Sources

Exterior Masonry Cladding and Stone Flooring:

Lorton Stone

Wood Block Flooring:

Kaswell

Floor and Wall Tile:

Stone Source, Daltile

Raised Flooring:

Formica

Exit Devices:

PRL, Von Duprin

Security Gates:

Cascade Coil

Locksets:

Schlage

Folding Panel Partitions:

Modernfold

Custom Woodwork and Paneling:

Jefferson Millwork

Paints and Stains:

Sherwin-Williams